Supply Chain Attacks: When Trusted Software Turns Malicious

Dr. Mark Graham

Why attackers weaponise the software you already trust

SolarWinds was trusted software running on 18,000 networks. Microsoft signed, security-approved, legitimate vendor credentials. Until it wasn’t.

The attackers didn’t break in through the front door. They poisoned the supply chain, turned trusted software into an exfiltration channel, and walked out with data from government agencies and Fortune 500 companies.

Your security stack saw Microsoft-signed software connecting to legitimate-looking infrastructure and said, “Fine, carry on.”

That’s the problem with trust-based security. Once something is trusted, it stays trusted until you discover it’s been compromised. By then, the data’s already gone.

I’ve spent 40 years watching security vendors sell the same promise: “Trust our signatures, trust our reputation database, trust our threat intelligence.” But supply chain attacks prove that trust is exactly what attackers exploit.

And it’s getting worse. The ICO reported a 44% increase in data breaches involving third-party suppliers in 2023. Not because companies are careless, but because trusted software is now the attack vector of choice. Third-party software security has become the primary attack vector, with vendor risk management failing to prevent data theft from compromised applications that already have trusted access.

When your security stack is trusted by default, attackers don’t need to break your defences. They just need to become trusted.

How do supply chain attacks steal data

I’ll be direct: your security tools are designed to trust legitimate software. Microsoft Word? Trusted. Salesforce? Trusted. Your finance system vendor’s software? Trusted.

That trust makes sense for business operations. You can’t run a company if security blocks every legitimate application. But it creates a fundamental vulnerability that attackers have learned to exploit.

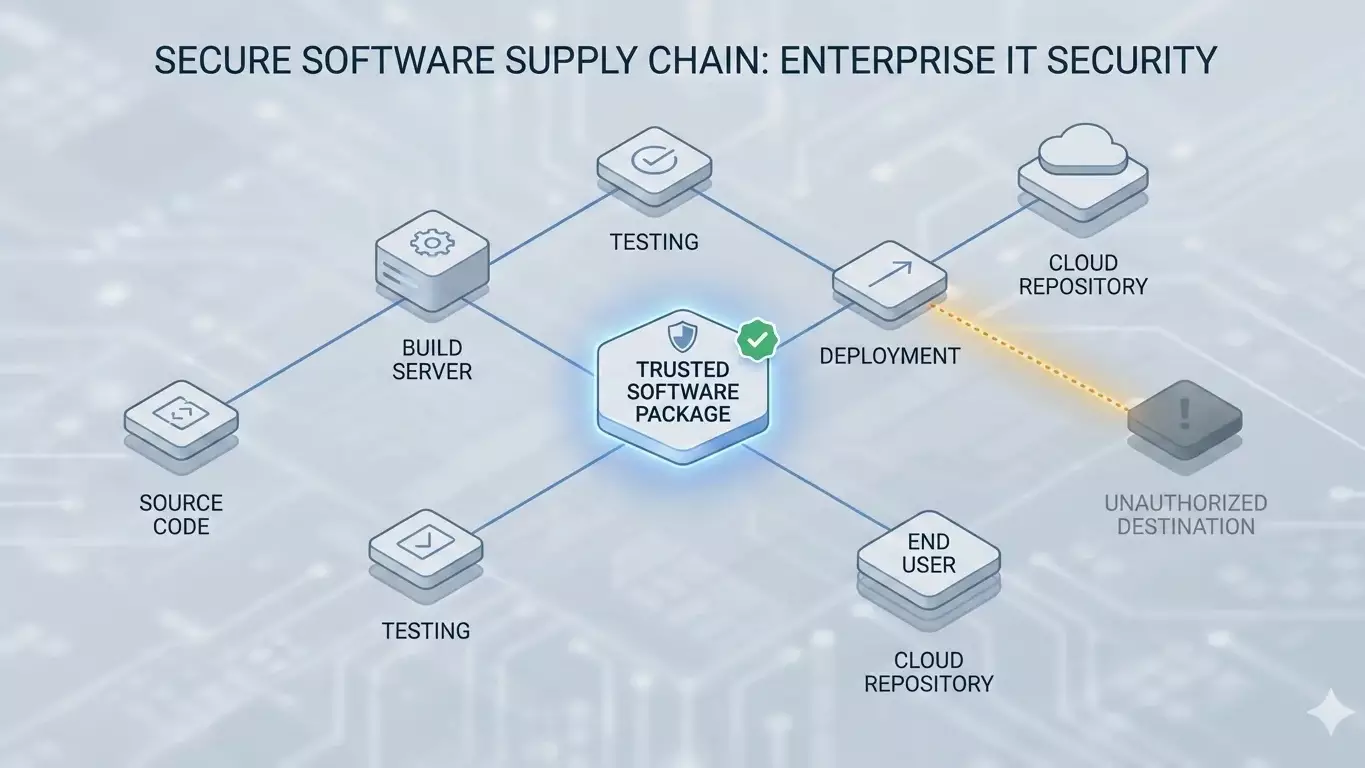

Here’s how it works:

Attackers compromise a software vendor’s build system. They inject malicious code into a legitimate software update. Your devices download the update because it’s signed by a trusted vendor. Your security stack sees valid signatures and allows execution.

Now the attacker has trusted software running on your devices with permission to transmit data wherever they want.

The British Library breach in October 2023 followed this pattern. Rhysida ransomware group didn’t smash through firewalls. They exploited trusted software pathways that security tools permitted because the software appeared legitimate.

Three months offline. Catalogue systems are down. Researcher access suspended. Not because they lacked security tools, but because those tools trusted the wrong things.

What your security stack actually validates

Your DLP, endpoint protection, and network security all validate different aspects of trust:

DLP validates: Email content, web uploads, and data classification policies. If data leaves via a desktop application like Word or Excel connecting directly to vendor infrastructure, DLP doesn’t see it. The data flow is outside DLP’s monitoring scope.

Endpoint protection validates: Application signatures, known malware patterns, and behaviour analysis. If the malicious code is signed by a legitimate vendor during a supply chain compromise, endpoint protection trusts it.

Network firewalls validate: IP addresses, port numbers, and protocol compliance. If Microsoft Word connects to an IP address, the firewall sees “outbound HTTPS traffic.” It can’t determine if that’s legitimate document syncing or data exfiltration.

None of these tools correlates which application process is transmitting data to which specific vendor infrastructure. They operate independently, validating different trust signals.

During a supply chain attack, all those trust signals look legitimate. Valid signatures, approved applications, and expected network protocols.

That’s why SolarWinds worked. That’s why the British Library breach worked. That’s why this attack pattern keeps succeeding.

What can't your security stack see during supply chain attacks?

Take this real scenario: Microsoft Word has been compromised through a supply chain attack. The application is still signed by Microsoft. Your endpoint protection still trusts it. But now it’s transmitting your business-critical application data to attacker-controlled infrastructure, and exploiting the application data protection gap that traditional security can’t see.

What does your security stack actually see?

Your DLP sees nothing because Word documents aren’t flowing through email or web gateways that DLP monitors. Application-to-cloud data flows are invisible to DLP.

Your endpoint protection sees Microsoft-signed Word.exe and permits execution. The signature is valid. The vendor is trusted.

Your firewall sees Word.exe connecting to an IP address and permits the traffic because Word needs internet connectivity for cloud features.

What your security stack cannot see: Word is connecting to infrastructure that isn’t owned by Microsoft. The destination IP address belongs to a different network entirely.

This is the validation gap that makes supply chain attacks so effective. Your security tools validate trust signals independently, but don’t validate the complete chain: this specific application should only connect to this specific vendor’s infrastructure. This is the application data protection gap at its most costly: without visibility into desktop application data security, panic shutdowns become inevitable.

What happens when you validate the destination infrastructure

Application-destination binding changes the security model fundamentally. Instead of trusting Microsoft Word to connect anywhere because it’s Microsoft-signed, you validate that Word only connects to Microsoft-owned infrastructure.

Here’s the validation:

Microsoft Word attempts to transmit data. We identify the application process through Application Process ID correlation. We extract the destination IP address from the network packet. We validate that the IP address belongs to Microsoft’s Autonomous System Number ranges.

ASN validation means checking which organisation actually owns the network infrastructure. It’s DNS-independent validation that works even when DNS is poisoned. Unlike traditional tools that query DNS servers, we verify actual network ownership. If Word tries to connect to infrastructure owned by anyone other than Microsoft, the transmission is blocked instantly through real-time prevention.

During the SolarWinds attack, compromised software connected to the attacker’s infrastructure that wasn’t owned by SolarWinds. The domain names looked legitimate. The DNS responses appeared valid. But the actual IP addresses belonged to networks controlled by attackers.

If you validate destination infrastructure ownership, the attack fails. Compromised Microsoft software cannot transmit to non-Microsoft infrastructure. Poisoned Salesforce updates cannot connect to destinations outside Salesforce’s network ranges.

The application trust signal is valid. The endpoint protection sees legitimate software. But the destination infrastructure validation fails because the data isn’t going where trusted software should send it.

That’s application-destination binding. Even if attackers compromise trusted software, they cannot use it to exfiltrate data to unauthorised infrastructure. This is how you prevent data theft during supply chain compromise: validate not just application signatures, but destination infrastructure ownership.

Why this matters for operational resilience

When the British Library discovered its breach, it shut down everything. Three months offline. Catalogue systems, researcher access, and digitisation projects were all suspended.

They had no choice. Without confidence about what data was at risk, which systems were compromised, or whether the attack was still active, shutdown is the only rational decision.

But what if they’d had process-to-destination visibility? What if they could answer: “Which applications transmitted data during the breach? Where did that data actually go? Was the destination legitimate vendor infrastructure or attacker-controlled?”

Strategic triage becomes possible. Isolate the compromised finance system that is connected to unauthorised infrastructure. Keep the catalogue system running because its connections went only to legitimate vendor destinations. Maintain researcher access to systems with verified data protection.

You don’t shut down everything. You shut down what needs stopping and keep operational what you know is safe.

That’s post-breach operational resilience during supply chain attacks. Not perfect prevention, but confident operational decisions during active incidents based on real-time prevention of unauthorised data flows.

The FCA’s operational resilience requirements recognise this reality. They’re not asking financial services firms to prevent all incidents. They’re asking firms to maintain important business services during incidents.

You cannot maintain services if you don’t know which applications are trustworthy during a supply chain compromise.

What supply chain immunity actually looks like

Let’s consider the technical specifics, because this isn’t theoretical.

Microsoft Word is authorised to transmit data. But only to IP addresses within Microsoft’s ASN ranges. If Word attempts to connect to infrastructure owned by Amazon, Google, Cloudflare, or any network that isn’t Microsoft’s, transmission is blocked. This instant threat prevention happens automatically. It’s a zero-touch security deployment that requires no user intervention or manual policy updates.

Salesforce CRM can sync customer data. But only to the Salesforce infrastructure. If a compromised Salesforce update tries to exfiltrate CRM records to attacker-controlled cloud storage, the destination validation fails.

Your finance system vendor’s software has legitimate reasons to transmit data. But only to their specific infrastructure. If a supply chain attack redirects that data flow to a different network, application-destination binding catches it.

This isn’t about blocking all data transmission. It’s about validating that trusted applications only connect to their legitimate vendor infrastructure, even when those applications have been compromised.

The attacker can compromise the software. They can inject malicious code. They can bypass endpoint protection with valid signatures. But they cannot change which network infrastructure they actually own.

And that’s what we validate.

How do you know if you're at risk from supply chain attacks?

Here’s what I tell every IT Director evaluating supply chain attack protection: you’re making trust decisions about application data flows right now. You just don’t realise you’re making them.

When Microsoft Word connects to the internet, your security stack trusts it. When Salesforce syncs CRM data, your firewall permits it. When your finance system transmits reports, your endpoint protection allows it.

Those trust decisions might be correct. Or they might be allowing supply chain compromises to exfiltrate your business-critical application data undetected. This is the application data theft prevention gap that costs companies months of downtime.

The British Library, SolarWinds, Kaseya, Codecov, all had security tools. All used trusted, legitimate software. All got compromised through supply chain attacks because their security stack validated trust signals independently, not the complete application-to-destination chain.

Give us 10 devices and 10 days. We’ll show you which applications on your estate are transmitting data, and where that data is actually going. Not theoretical risk. Actual data flows from Word, Excel, CRM systems, and finance applications.

Most organisations discover that 15-30% of application traffic goes to destinations they hadn’t authorised or didn’t know about. Not malicious necessarily, but unmonitored. During a supply chain attack, that unmonitored traffic could be the exfiltration channel.

Then you decide. Validate destination infrastructure and gain supply chain attack immunity, or accept the risk that trusted software might be compromised and you won’t detect it.

At least you’ll understand the risks that exist. Most companies don’t realise they have this validation gap until they’re in the middle of a supply chain breach, making shutdown decisions with no confidence about what data left the building. Don’t risk being the next British Library.

What needs to change in security thinking

The industry needs to stop assuming that trust is binary. Trusted software, untrusted malware. Legitimate vendors, malicious attackers.

Supply chain attacks prove that’s not how the real world works. Trusted software can be compromised. Legitimate vendors can be breached. Valid signatures can be weaponised.

The question is what happens when trust fails?

The assume breach strategy recognises this reality: build for what happens after prevention fails, not if.

Right now, the answer is panic shutdowns because companies have no visibility into application-to-destination data flows. Security tools validate trust signals independently, but can’t detect when trusted applications connect to unauthorised infrastructure.

Application data theft prevention complements your existing security stack by adding the validation layer that those tools don’t provide, giving you automated data protection with forensic data visibility that shows exactly which application transmitted what data where. Not replacing DLP, which protects email and web data brilliantly. Not replacing endpoint protection, which defends devices from malware.

Filling the gap between the application process and destination infrastructure. The correlation that enables you to detect supply chain compromises even when all the trust signals appear legitimate.

Because the alternative is watching more companies shut down for months after supply chain breaches, destroying revenue and customer confidence, all because they trusted the wrong things at the wrong time.

After 40 years of building security systems, I can tell you: application-destination binding is solvable.

We just need to stop pretending that trust alone is sufficient protection.

Your Questions Answered

Q. Don’t endpoint protection tools catch supply chain attacks?

Endpoint protection catches known malware and suspicious behaviour. During supply chain attacks, the malicious code is signed by legitimate vendors and behaves like normal software. Endpoint tools trust it because the trust signals appear valid.

Q. Can DLP prevent supply chain attacks?

No. DLP monitors email and web traffic, but doesn’t validate which application process is transmitting to which destination infrastructure. During supply chain attacks, compromised desktop applications bypass DLP entirely because they don’t use email or web gateways. You need application data theft prevention that correlates application behaviour with destination infrastructure.

Q. Can’t firewalls block unauthorised destinations?

Firewalls operate at the network layer and can block IP addresses or domains. But they cannot correlate which application process is transmitting to which destination. During supply chain attacks, the destination might appear legitimate because DNS has been poisoned, or the application is using vendor infrastructure initially before redirecting data.

Q. What is application-destination binding?

Application-destination binding validates that each application only transmits data to its legitimate vendor’s infrastructure. Microsoft Word can only connect to Microsoft-owned networks. Salesforce can only sync to the Salesforce infrastructure. Even if attackers compromise the application with valid signatures, they cannot redirect data to infrastructure they don’t control. This prevents supply chain attacks from exfiltrating data through trusted software.

Q. What about zero-trust architecture?

Zero-trust validates user identity and device compliance before granting access. Excellent for access control. But once access is granted and trusted applications are running, zero trust doesn’t validate destination infrastructure for application data flows. Supply chain attacks operate within the trusted environment.

Q. Does this replace my existing security stack?

No. Application data theft prevention complements your existing DLP, endpoint protection, and network security. Your DLP continues protecting email and web data. Your endpoint protection continues defending against malware. ZORB fills the application-to-destination validation gap that your current stack doesn’t cover.

Q. How long does a supply chain attack assessment take?

A proof-of-value assessment runs for 10 days across 10 devices in your environment. You’ll see actual application data flows – showing you which applications are transmitting data, where it’s going, and whether destinations match legitimate vendor infrastructure. No disruption to operations, no software changes required during discovery mode.

Q. What’s the difference between DLP and application data theft prevention?

DLP protects email and web data from accidental exposure. Application data theft prevention protects desktop application data from deliberate theft during security incidents. DLP operates at email gateways and web proxies. Application data theft prevention correlates the application Process ID to the destination IP address, detecting when compromised applications attempt unauthorised data transmission. You need both. They protect different data flows in your environment.

Dr Mark Graham is leading authority on application data theft and exfiltration techniques. His PhD in malware detection in network traffic and almost 40+ years in cybersecurity led to the formation of ZORB Security. ZORB is an alumni of the NCSC for Startups accelerator. ZORB works with professional services, financial services, legal firms, software houses and educational organisations to solve the application data protection challenge.