DNS poisoning: Why Microsoft, Symantec and ProofPoint can't prevent application data theft

Dr. Mark Graham

When your DLP vendor trusts DNS, attackers control your application data theft prevention

On October 22, 2025, security researchers disclosed CVE-2025-40778 – a critical flaw affecting 706,000 DNS resolvers worldwide. Within days, a public proof-of-concept demonstrated how attackers could poison DNS caches and redirect internet traffic to malicious infrastructure. Any security tool that trusts DNS responses to validate destinations became vulnerable overnight. This includes Microsoft Defender, Symantec DLP, and ProofPoint.

This followed on the back of the November 2024 StormBamboo attack, where threat actors compromised a US internet service provider and used DNS poisoning at the ISP level. Every organisation routing DNS queries through that ISP, regardless of their enterprise security stack, had their business-critical application data redirected to the attacker’s infrastructure.

These aren’t small vendors with sloppy architecture. These are enterprise-grade security platforms trusted by thousands of organisations. Yet when DNS infrastructure is compromised, their application data theft prevention fails completely.

Not because they built bad products. Because they built them on an architectural assumption that no longer holds: that DNS can be trusted.

This isn’t just a technical vulnerability. It’s why organisations lose post-breach operational resilience, which is the ability to make strategic decisions during active security incidents. Without confidence about what data is actually being stolen, a shutdown becomes your only option.

I’ve spent 40 years in cybersecurity. I’ve watched this pattern repeat across every “next-generation” security technology. We build tools assuming one layer of infrastructure will remain secure. Then attackers compromise that layer, and everything built on top of it fails.

Perimeter security assumed the network boundary would hold. It didn’t. Endpoint detection assumed devices would remain uncompromised. They don’t.

Now we’re learning that DNS-dependent security assumes DNS infrastructure can be trusted. It can’t.

How DNS poisoning defeats DLP and forces panic shutdowns

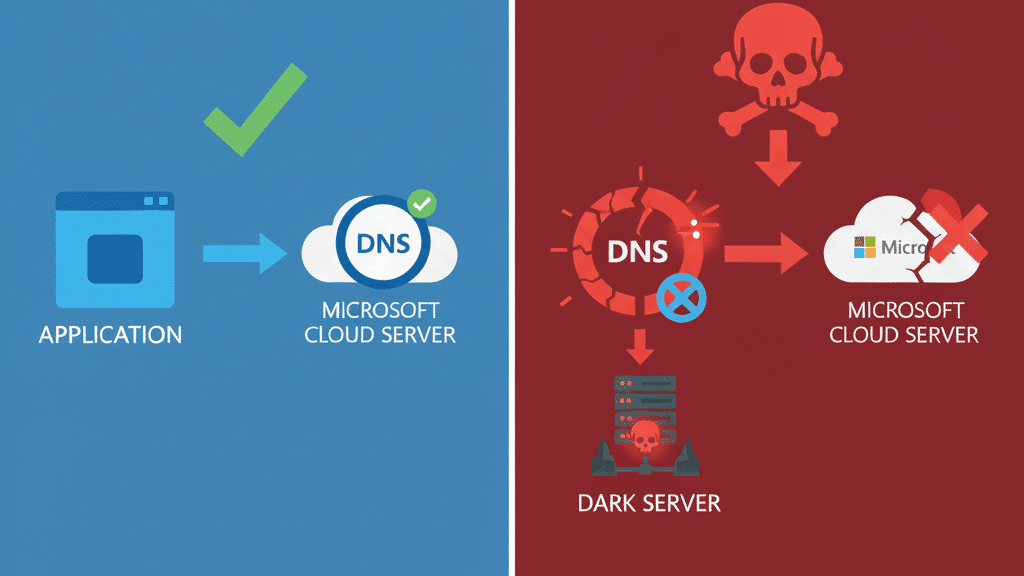

DNS works like a phone directory for the internet. When Microsoft Word wants to upload a document to OneDrive, it asks DNS: “Where is onedrive.microsoft.com?” DNS responds with an IP address, and Word sends your data there.

Your DLP monitors this. It sees Word requesting “onedrive.microsoft.com” and thinks: “Microsoft domain, legitimate vendor, approved for business use.” Traffic allowed.

But what doesn’t your DLP see: whether DNS told the truth about the destination.

This isn’t theoretical. In October 2025, the BIND vulnerability exposed 706,000 DNS resolvers to cache poisoning attacks. Earlier that year, StormBamboo compromised ISP infrastructure and intercepted DNS queries, returning attacker-controlled IP addresses instead of legitimate vendor infrastructure. In both cases, Microsoft Word still requested “onedrive.microsoft.com”. DNS still returned an IP address. But that IP belonged to attackers, not Microsoft.

From your DLP’s perspective, nothing looked wrong. Domain request? Legitimate. DNS response? Received. Traffic allowed. Your DLP never questioned whether the IP address actually belonged to Microsoft. Because DLP tools don’t validate destination infrastructure, and they trust DNS to do that.

When DNS lies, DLP believes it. Desktop application data walks out “legitimately” to the attacker’s infrastructure through unauthorised data transmission that bypasses every security control.

This is the application data protection gap that forces panic shutdowns during incidents. Without confidence about which applications are transmitting data to attackers versus legitimate vendors, you can’t make strategic decisions. You shut everything down.

That’s not a security failure. That’s operational reality when prevention fails.

What big vendors won't tell you about their DNS dependency

Microsoft, Symantec, and ProofPoint don’t advertise that their data exfiltration prevention depends entirely on DNS integrity. Because admitting that dependency means admitting vulnerability.

Their marketing talks about “advanced threat protection” and “next-generation DLP”. What they don’t mention: when DNS poisoning attacks occur, their protection becomes useless.

It’s not that their products are badly designed. It’s that they’re designed for a threat model that assumes DNS could be trusted. That assumption is wrong, and has been wrong for years. We just keep pretending it isn’t.

DNS is often the only validation layer. And when DNS is compromised, that single point of trust fails. DLP sees: “Word uploading to microsoft.com”. The reality is: Word uploading to an attacker’s infrastructure.

DNS poisoning isn’t a new attack vector. Neither is BGP hijacking. Nor are ISP compromises. Yet we continue building security tools that trust these infrastructures to remain secure.

The BIND vulnerability affecting 706,000 resolvers? That’s just the most recent public proof that DNS cannot be relied upon for security decisions. StormBamboo demonstrated it at the ISP level. Countless other attacks exploit the same fundamental weakness.

Every security tool that queries DNS to validate destinations has this dependency. Most IT Directors don’t realise their expensive enterprise DLP has this blind spot. CISOs discover it during incidents, when it’s too late to do anything about it.

Why M&S was offline for months: The confidence gap

When Marks & Spencer detected their breach, they faced the same question every compromised organisation faces: “What data is being stolen right now?” Their DLP couldn’t answer. It showed domain requests to legitimate vendors. But if DNS was compromised, those “legitimate” destinations could be attacker infrastructure.

No confidence = no strategic incident response. Just binary decisions: keep everything running and risk ongoing theft, or shut everything down and accept revenue destruction.

M&S chose to shut down. Customer service went offline. Online operations stopped. Not just for days, but for months. The shutdown destroyed more business value than the breach itself.

This is the cost of the application data protection gap. Not the initial breach. The extended operational disruption occurs because you can’t distinguish legitimate application behaviour from data exfiltration during an active incident.

Strategic shutdown vs panic shutdown isn’t about better threat detection. It’s about having confidence in what data is actually at risk, so you can make measured operational decisions instead of wholesale shutdown responses.

DNS-independent validation: Real-time application data theft prevention that works when DNS is compromised

ZORB doesn’t query DNS. At all.

We validate the actual destination IP address in the packet against known vendor infrastructure ranges. We don’t care how the application obtained that IP, be it through DNS, hard-coded, or carrier pigeon. We verify the destination IP belongs to the legitimate vendor’s Autonomous System Number (ASN).

This is process-to-flow visibility, i.e. correlating which application Process ID is sending data to which destination IP. If Microsoft Word tries to send data to an IP address outside Microsoft’s ASN ranges, we block it. Immediately. Before data leaves the device.

DNS can be completely poisoned, returning attacker IPs for every query. Doesn’t matter. We’re not asking DNS where data should go. We’re validating where data is actually going against known vendor infrastructure.

This is real-time prevention that works regardless of DNS integrity. When DNS poisoning redirects Word to an attacker’s infrastructure, we see the destination IP mismatch and block transmission. The application still thinks it’s talking to Microsoft. But the data never leaves.

During a StormBamboo-style attack where DNS is compromised:

DLP sees: Word → “onedrive.microsoft.com” → DNS returns IP → Traffic allowed → Data stolen

ZORB sees: Word → Destination IP: 45.67.89.10 → Not in Microsoft ASN ranges → Transmission blocked

This capability delivers post-breach operational resilience by giving you confidence about application data during incidents. You know Word can only send to the Microsoft infrastructure. Excel can only send to approved cloud storage. CRM systems can only transmit to their vendor’s ASN ranges.

That confidence changes incident response from “shut everything down immediately” to “isolate compromised systems, maintain operations on protected applications.”

Why this matters for operational continuity during an attack

The ability to make strategic decisions during security incidents requires knowing what’s actually happening to your data. Most organisations don’t have that visibility. When incidents occur, IT Directors face pressure from the board: “Are we losing customer data right now?” Without confident answers, the only defensive response is shutdown. Stop all application data flows. Kill customer-facing services. Halt operations.

But if you had confidence that business-critical application data cannot be exfiltrated, even during active DNS poisoning, even with compromised vendor software, operational decisions change completely.

Finance systems with sensitive data? Yes, isolate those during the investigation.

Customer portals that maintain service level agreements? Keep them running. You know their application data is protected.

Revenue-generating platforms your competitors would love to see offline? Maintain operations with confidence.

This isn’t reckless. This is strategic incident response enabled by actually knowing what data is at risk instead of assuming the worst case for everything.

Revenue protection during incidents comes from selective operational maintenance, not wholesale shutdown. You stay operational longer because you can make granular decisions. You recover faster because you can restart systems with confidence about what data is left in the building.

That’s operational resilience. It’s not “better security” or “faster detection”. It’s a fundamentally different capability during incidents.

What this means for your organisation

The BIND vulnerability disclosed in October 2025 has a public proof-of-concept. That meant that attackers don’t need to discover the technique, as it’s already documented and available. The 706,000 exposed DNS resolvers represent organisations worldwide, many of which route their DNS queries through vulnerable infrastructure without realising it.

StormBamboo compromised one ISP. But the architectural vulnerability they exploited exists everywhere DNS is trusted for security decisions.

Every organisation that routes DNS queries through ISP infrastructure faces this risk. Every DLP that validates destinations through DNS queries has this dependency. Every security stack that trusts DNS responses to verify legitimate traffic has this weakness.

You can’t prevent DNS compromise. ISPs get breached. BGP gets hijacked. DNS cache gets poisoned. DNS resolvers have exploitable vulnerabilities. These attacks work because the internet wasn’t designed with security as its primary requirement.

You can prevent DNS compromise from becoming application data theft.

Beyond DNS: Why application process-driven security is the only reliable approach

DNS-independent validation solves one attack vector. But the fundamental requirement is process-to-destination correlation – knowing which specific application is sending what data where.

Firewalls see IP addresses but can’t identify source applications. DLP sees application requests but trusts DNS responses. Endpoint protection detects malware but doesn’t prevent data transmission from legitimate applications being abused.

None of them correlates the application Process ID to the destination infrastructure. That’s the gap.

When you have that correlation, everything changes:

- Microsoft Word is blocked from sending to non-Microsoft IPs

- Salesforce is restricted to the Salesforce infrastructure only

- Excel was prevented from uploading to the attacker-controlled cloud storage

- Finance applications are limited to their vendor’s verified ASN ranges

This is automated data protection that operates in real-time without user intervention. No configuration when DNS changes. No updates when vendors modify infrastructure. Just continuous validation: Does this destination IP belong to this application’s vendor?

If yes, transmit. If no, block and alert.

Supply chain attack immunity comes from this validation. Even if attackers compromise Microsoft Word itself and try to exfiltrate to their infrastructure, destination validation catches it. Trusted application, unauthorised destination = blocked.

This complements endpoint protection perfectly. Your EDR detects and remediates malware. ZORB prevents data theft during the window between infection and remediation. Defence-in-depth without overlap.

What to do right now

Your current DLP vendor probably won’t discuss their DNS dependency. Security vendors don’t like advertising architectural vulnerabilities that can’t be fixed without a fundamental redesign.

But you need to understand the risk in your own environment. Not the theoretical vulnerabilities, but actual unauthorised application data flows that exist right now.

Request a proof-of-value assessment. We deploy DataShield agents in discovery mode on 10 devices for 10 days. Zero disruption. Zero risk. Just visibility into what application data is actually flowing.

You’ll see which applications are transmitting data via DNS queries to ISP infrastructure instead of directly to vendors. Where the risk of DNS redirection exists in your specific environment. What desktop application data security gaps are your current DLP not covering?

Then you decide. Fill the gap or accept the risk.

But at least you’ll know what you’re accepting. Most IT Directors don’t realise they have an application data protection gap until they’re mid-incident, watching customer data walk out while their expensive DLP reports “all legitimate traffic”.

Don’t wait to discover your DNS dependency during an active breach.

What changes when DNS can't defeat your protection

Strategic incident response. Faster recovery. Revenue protection during attacks. Competitive advantage when others are offline.

These aren’t marketing claims. These are operational outcomes that become possible when you know business-critical application data cannot be exfiltrated – regardless of DNS integrity, regardless of which security layers attackers compromise.

After 40 years of building security systems, I learnt that an assume breach strategy works only if you build for what happens when prevention fails. DNS-dependent security assumes DNS won’t fail. That assumption is wrong.

ZORB was built assuming that DNS would be compromised. ISPs will be breached. Vendor software will be weaponised. These aren’t doomsday predictions; they’re documented attack patterns happening now.

The question isn’t whether attackers will poison DNS. The question is whether your application data theft prevention keeps working when it does.

Your Questions Answered

Q: What is DNS poisoning, and how does it affect data protection?

DNS poisoning (also called DNS spoofing) redirects trusted applications to attacker-controlled infrastructure by corrupting DNS responses. DLP trusts these DNS responses, allowing business-critical data to be transmitted to attackers while reporting “legitimate traffic.”

Q: How can I prevent data theft when DNS is compromised?

Use DNS-independent validation that verifies destination IP addresses against vendor infrastructure ranges, not DNS responses. This prevents data exfiltration even when DNS poisoning attacks successfully redirect applications to the attacker’s infrastructure.

Q: Does this mean my DLP is useless?

No. Your DLP handles email and web data loss prevention brilliantly. That’s what DLP was designed to do. DNS-independent validation fills the application data gap your DLP was never meant to cover. You need both.

Q: Can DNS poisoning really affect enterprise networks?

Yes. The October 2025 BIND vulnerability affected 706,000 resolvers globally. StormBamboo compromised ISP-level infrastructure. These aren’t small-scale attacks; they are infrastructure compromises that affect thousands of organisations simultaneously.

Q: Do I need to replace my existing security stack?

Absolutely not. Application data theft prevention complements your existing DLP, EDR, and firewall. It doesn’t replace them. You’re filling a gap, not ripping and replacing. Your current security investment continues to protect what it was designed for.

Q: How quickly can DNS poisoning attacks happen?

Instantly. Once the DNS infrastructure is compromised, every query through that resolver returns attacker-controlled addresses. Your applications continue working normally, but they just send data to the wrong destination. Real-time prevention is the only defence.

Q: What’s the actual business impact of DNS-dependent security?

Extended shutdowns when you can’t distinguish legitimate application behaviour from data theft. M&S was offline for months. JLR production stopped. Knights of Old forced into administration. The shutdown costs more than the breach. That’s the DNS dependency cost.

Q: Can I test this in my environment before committing?

Yes. The proof-of-value assessment shows real application data flows in your environment. It shows what’s going directly to vendors versus routing through ISP infrastructure. No obligation. Just evidence of the gap that exists right now.

Dr Mark Graham is founder and CEO of ZORB Security. His PhD focused on malware detection. He has spent four decades building cybersecurity systems for enterprise organisations. ZORB is an alumni of the NCSC for Startups accelerator. ZORB works with professional services, financial services, and healthcare organisations to fill the application data protection gap.